Sentiment Distribution

Filter by Sentiment

Toggle sentiments to show/hide in the chart below

Top 20 Brands by Mention Count

Click any segment to see the actual Reddit comments

Select a segment above to view mentions

| Context | Text | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Click a chart segment to filter mentions | ||

The Question

Is Sweetgreen a hidden value stock poised to benefit from GLP-1 medications, changing eating habits, and the “protein everything” era?

To find out, I decided to extract brand mentions (with sentiment) from r/Ozempic posts to understand what products people on GLP-1 medications are actually discussing.

Simple enough, right? Not exactly.

The Messy Reality of LLM-Powered Data Extraction

My original intention was to demonstrate how LLMs make it possible to explore datasets faster than ever. But I quickly ran into something many practitioners already know: there’s a significant gap between getting something that looks good and getting something that’s actually production-grade.

The dataset: Several months of posts (with comments) from r/Ozempic on Reddit.

Iteration #1: The “Automagic” Approach

My first pipeline was straightforward:

- Extract Reddit data to JSON with PRAW (Python Reddit API Wrapper)

- Use Claude CLI to find brands, attach sentiment, output to a second JSON file

- Transform results for visualization

Step 1 was smooth. Step 2? Not so much.

Claude decided to do simple keyword matching based on a list of brands it generated on the fly. Worse, it silently sampled the data instead of evaluating every post. That wasn’t going to scale if I wanted repeatable results.

Iteration #2: Batch to Claude API

Next: send batches to the Claude API for brand + sentiment extraction.

The problem? 1,000 posts with 10+ comments each is a lot of tokens. Processing in small batches (10 posts each) meant repeating prompt instructions ~100 times. By batch 8, I was already at $0.20 in API costs. Shut it down.

Iteration #3: Local Ollama Model

To avoid API costs entirely, I switched to running Llama 3.1 8B locally via Ollama. On an Intel Mac, batch 1 of 50 took so long I thought the process had frozen. Local models weren’t going to work for this dataset size.

Iteration #4: Free OpenRouter Models

With an assist from a friend, I discovered OpenRouter, which offers free tiers for models like Gemma and Mistral. This solved my cost problem but surfaced a new one…

The Chipotle Paradox

When I removed brand name examples from the prompt (to avoid biasing the model), the LLM missed obvious mentions like “Chipotle.”

When I added brand examples back, Chipotle became suspiciously overrepresented—explicitly-stated brands were found, but others were overlooked.

What I needed was a way to create a comprehensive brand dictionary without biasing results. But how? Vanilla spaCy models aren’t robust enough for this task, and there’s no comprehensive database of “every brand, product, and company.”

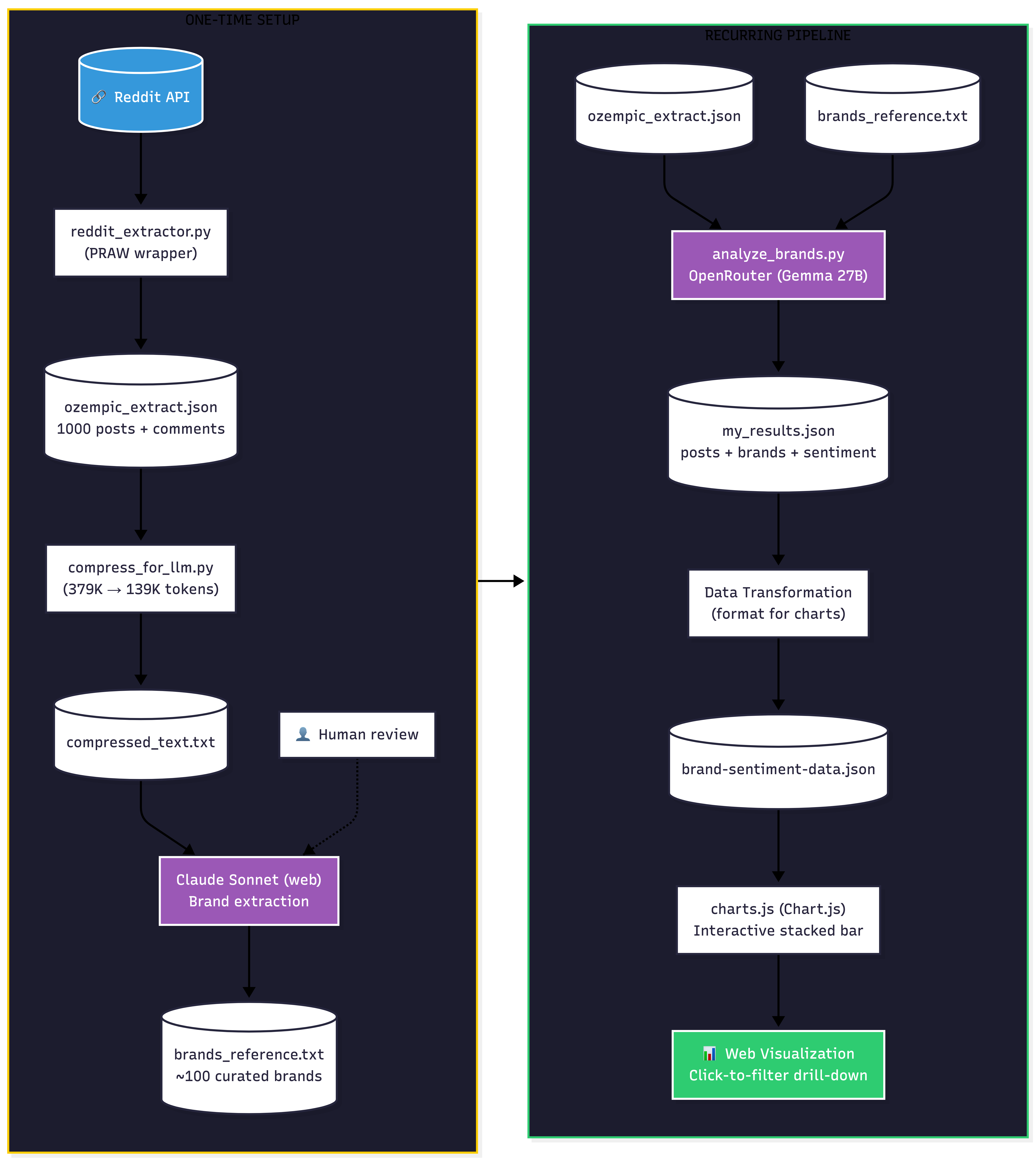

Iteration #5: The Final Pipeline

Not the most elegant solution, but it worked:

Step 1: Compress the data

- Strip metadata (IDs, scores, URLs)

- Filter to high-quality content (upvoted comments only)

- Reduce from 379K tokens to 139K tokens

Step 2: One-time powerful LLM pass

- Pass compressed text through Claude (via web interface)

- Extract ALL brand names found

- Output:

brands_reference.txt

Step 3: Use reference list in batch processing

- Feed the brand list back into the extraction prompt

- Prompt says: “Look for these known brands, AND any others you find”

One discovery: I had to repeatedly prompt Claude with “Are you sure you didn’t miss anything? Do another pass.” to get comprehensive coverage.

The final architecture looked like this:

Key Takeaways

- LLMs are powerful but need guardrails — Silent sampling and lazy keyword matching are real failure modes

- Token economics matter — Batch processing at scale requires careful cost-benefit analysis

- Hybrid approaches win — Using a powerful model for dictionary generation + cheaper models for batch extraction

- Perfect is the enemy of good — Even with optimizations, there’s variance between models. At some point, “good enough” is the right call.

The Answer

No matter how I sliced the data… ain’t nobody talking about Sweetgreen.

But the journey taught me more about production-grade NLP pipelines than any tutorial could.